![]() ROHM introduces a compact evaluation kit to demonstrate the high performance of the company’s 4th generation SiC MOSFETs in a state-of-the-art Totem Pole PFC. In addition to showing key performance metrics such as efficiency measurements the paper describes some design challenges of the topology at hand and how they were addressed in order to obtain a PFC with universal input.

ROHM introduces a compact evaluation kit to demonstrate the high performance of the company’s 4th generation SiC MOSFETs in a state-of-the-art Totem Pole PFC. In addition to showing key performance metrics such as efficiency measurements the paper describes some design challenges of the topology at hand and how they were addressed in order to obtain a PFC with universal input.

The Totem Pole PFC (TP-PFC) topology as such has been discussed in multiple articles in the past [1]. With the availability of WBG semiconductors that feature high performant body diodes it is becoming very attractive. Its key advantage over the traditional boost PFC is that it eliminates low frequency rectification and the power loss associated with the forward drop of a 50 Hz rectifier. Thus, efficiencies above 98% can be achieved and, if a suitable secondary stage with a similar efficiency is used, the 80+ Titanium target efficiency can be reached.

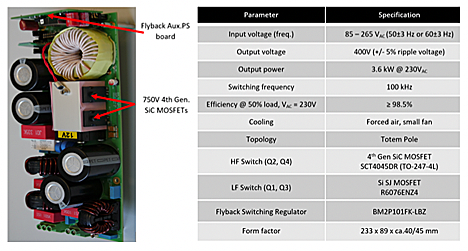

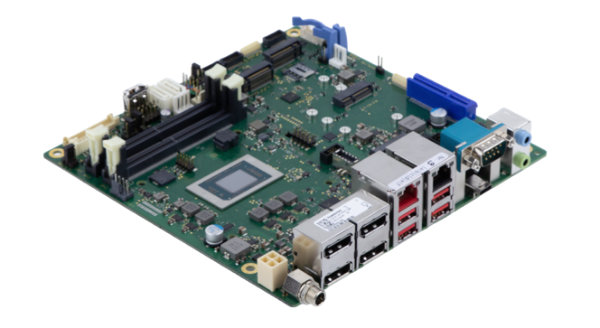

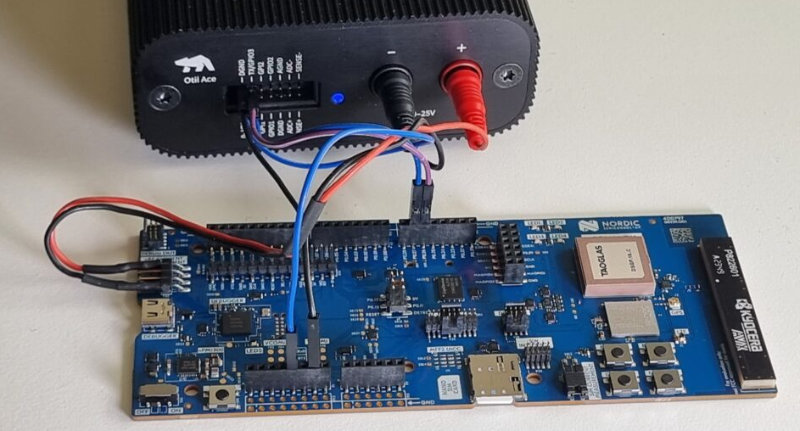

In Figure 1, a picture of the featured evaluation kit (EVK) that implements the TP-PFC with rated input current of 16A is provided alongside some of the design specifications. The key devices in use in this board are highlighted in Figure 1. In addition to 4th Generation SiC MOSFETs this design uses ROHM Si SJ MOSFETs, as well as the gate drivers BM61S41/BM61M41 and other components from ROHM, such as the shunt resistor and the flyback switching regulator IC in the auxiliary power supply.

Figure 1 – TP-PFC EVK and specifications.

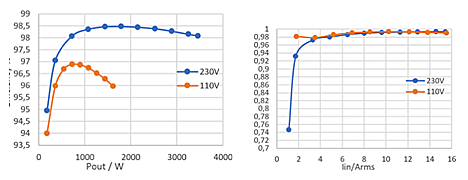

The performance of the developed EVK is illustrated in the following plots showing the measured efficiency and the achieved input power factor at both 230V and 115V AC input. Regarding the efficiency, it should be noted that this includes all on-board power consumption of the auxiliary power supplies for the gate drivers, the low voltage electronics, and the cooling fan. It can be seen that the requirement of a power factor > 0.95 at 20% load is reached. If the PFC circuit is combined with a DC/DC stage of suitably high efficiency the design can also meet the efficiency requirements of 80+ Titanium.

The following paragraphs discuss how this design has been developed and how certain challenging aspects of this topology were addressed. Amongst these challenges are:

- Finding the correct settings for blanking and deadtime.

- Safe automatic start-up on the grid's universal input voltage.

- Soft start around the AC zero-crossing to minimize current spikes.

Beforehand, the benefits of ROHM’s 4th generation SiC MOSFETs are going to be highlighted.

ROHM 4th GENERATION SiC MOSFET

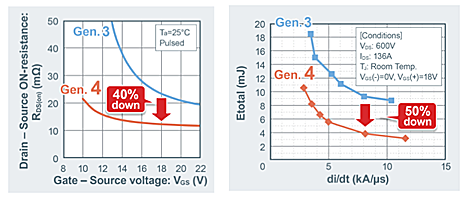

The new SiC MOSFETs realize a substantial reduction of 40% in the on-state resistance per unit area compared to the 3rd generation SiC MOSFETs. This reduction is achieved without sacrificing short circuit robustness – making the new devices extremely high performing and robust.

In addition, the switching losses in the 4th generation SiC MOSFETs are 50% less than in the 3rd generation thanks to a drastically reduced gate-drain parasitic capacitance “CGD”. This translates to a higher conversion efficiency.

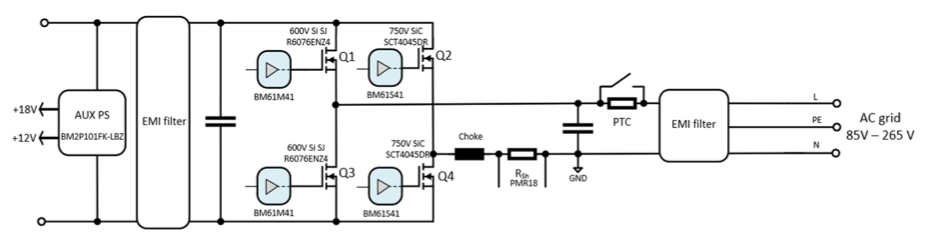

Figure 2: TP-PFC circuit diagram.

For driving the gate, in contrast to the 18V gate-source voltage “VGS” required in the 3rd generation and earlier SiC MOSFETs, the new products support a more flexible gate voltage range (15-18V). In addition, due to the reduction in the “CGD” parasitic capacitance and hence the CGS to CGD ratio, the 4th generation SiC MOSFETs can be safely turned off with just 0V without parasitic turn-on that may be caused by a high dVDS/dt. As a result, the gate driver circuit can be simplified by eliminating the need for a negative bias for turn off.

Figure 3- Measured efficiency and power factor: a) Measured efficiency (left), b) Measured power factor (right).

Figure 4: On-state resistance and switching loss reduction in ROHM's 4th generation SiC MOSFETs. On state resistance reduction in 4th generation SiC MOSFETs (left), Switching loss comparison 3rd vs 4th generation SiC MOSFETs (right).

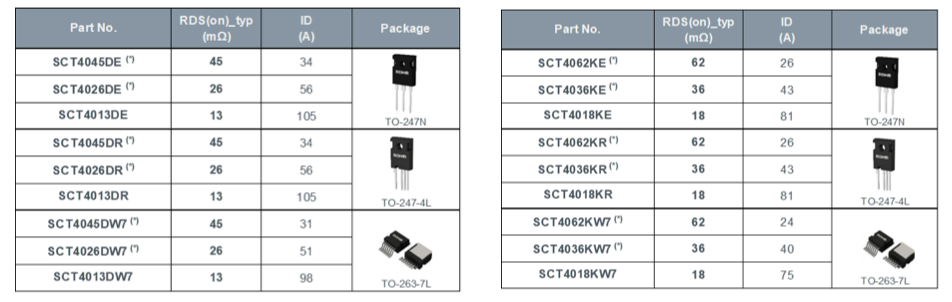

Table 1 shows ROHM’s 750V and 1200V 4th generation SiC MOSFET line up. The devices are available in THD-through hole TO-247N and TO-247-4L as well as in the SMD version TO-263-7L. The automotive qualification is planned for all devices marked with an asterisk (*).

Table. ROHM’s 4th generation SiC MOSFETs line up: 750V MOSFET line up on the left, 1200V MOSFET line up on the right.

BLANKING AND DEAD TIME SETTING

The errors associated with the AC zero-crossing detection as well as the parasitic elements of the MOSFETs must be taken into consideration when setting the PWM control. In this TP-PFC EVK, a 50µs blanking time has been inserted around the AC zero-crossing. During which, the four switches are turned OFF shortly before the zero-crossing, either from positive to negative or from negative to positive, to prevent shoot-through. The control loop is frozen during this time to prevent the integrator build-up from causing an unwanted high current spike by applying a large PWM pulse in the next turn on. A short blank time enables higher controllability over the current waveform, lower THD and relatively higher efficiency. However, the minimum blanking time is limited by the controller sampling rate and the line frequency.

In addition to the blanking time around the AC zero-crossing, a suitable dead time must be set between the control commands of the complementary SiC MOSFETs. From the BM61S41 gate driver datasheet, the propagation delay has a maximum value of 65ns. Adding another 10ns max for the PWM propagation mismatch results in an absolute minimum dead time of 75ns. To account for the turn-off and turn-on delays of the SiC MOSFETs and to have some margin, the dead time for this board was set to 150ns. Of course this needs to be evaluated for each design and is also impacted by the selection of turn-on and turn-off gate resistances.

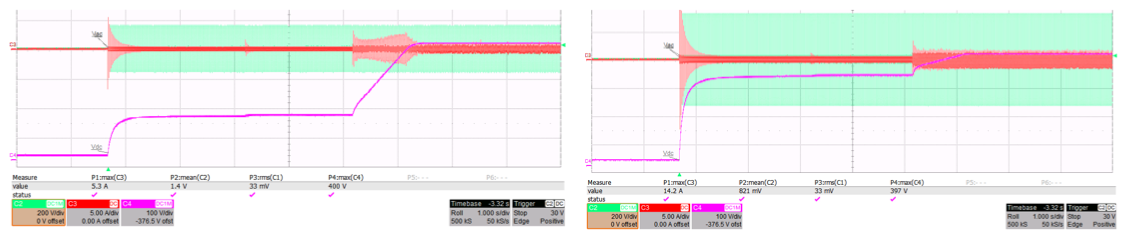

AUTOMATIC START-UP ON A UNIVERSAL GRIP INPUT

The TP-PFC EVK is equipped with a PTC for pre-charge in parallel with a bypass relay. At start-up, the relay is turned off and the bulk capacitors are pre-charged through the PTC to a safe threshold before turning on the relay and operating the converter. This prevents a circuit damage due to high inrush currents. The EVK was tested over the full universal input range [85Vac-265Vac] and has been proven to be safe for an automatic start up even at 265Vac. Thanks to the implemented Second Order Generalized Integrator - Frequency Locked Loop (SOGI-FLL), this EVK is also able to track and detect drifts in the grid’s frequency of 50±3 Hz or 60±3 Hz.

Figure 5: PFC automatic start-up vs AC input voltage. Left: Automatic start-up 110Vac, 400Vdc, right: Automatic start-up 230Vac, 400Vdc.

MEASURES TO MINIMIZE CURRENT SPIKES FOLLOWING AC ZERO-CROSSING

In the TP-PFC topology, the MOSFET’s switching sequence is of the essence. A failure to understand and observe the control challenges in a TP-PFC can lead to improper operation, unexpected EMI issues or even failure of the power devices. The most common challenge that is inherent to this topology is the occurrence of current spikes at the AC zero-crossing [2],[3]. These are mainly caused by the output parasitic capacitor “COSS” and the associated reverse recovery charge “Qrr” of the line frequency switched MOSFETs, which are only changing state on the AC zero-crossing. A detailed analysis of the AC current spikes and waveforms in a TP-PFC topology is presented in [2].

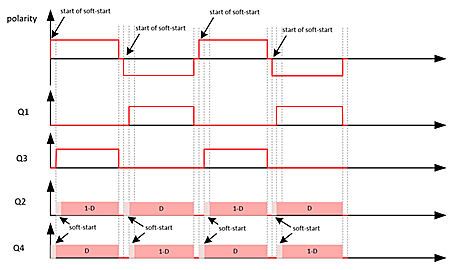

In ROHM’s TP-PFC EVK a soft-start sequence is implemented after every AC zero crossing. This involves a ramping of the duty cycles applied to the high frequency SiC MOSFETs (Q2, Q4) and fine control over the turn-on of the low frequency Si SJ MOSFETs. The implementation of this soft start achieved significantly reduced current spikes. The implemented MOSFET’s switching sequence is shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: MOSFETs soft start in TP-PFC.

The MOSFETs Q2 and Q4 are complementary switched. During the negative half cycle, the Q2 MOSFET is the active switch which is controlled by the calculated duty cycle “D”. During this time, the Q4 MOSFET is operating in synchronous rectification mode at “1-D” duty cycle. Note that the Q1 MOSFET is only switched at the grid’s frequency and stays on during the full negative half cycle to provide a low impedance return path to the mains. The operation reverses again during the positive half cycle and the high side and low side MOSFETs of each leg interchange their function.

As the input voltage changes polarity from negative to positive half cycle, and right after the AC zero crossing, the soft start sequence of the Q4 MOSFET kicks in. This sequence consists of applying an increasing factor to the pulse width in a way that gradually increases the on time of this MOSFET from 0% to 100% of the calculated “D”-cycle. While doing this, the Q1 MOSFET completely reverse recovers and the “VDS” of Q3 reduces to ground. Thus, the positive current spike, caused by the slow recovery of Q1 and the high “VDS” voltage across the Q3 MOSFET, is eliminated.

Knowing that the AC voltage is very low right after the zero crossing and since the inductor is already charged to the DC bus voltage, a large negative reverse current will flow through the inductor back to the mains. This leads to a high negative current spike when turning on the Q2 synchronous MOSFET even at “1-D” duty cycle. Therefore, once Q4 reaches the full “D”-cycle, the soft start is also applied to the Q2 synchronous MOSFET to reduce this negative spike to near zero. Simultaneously, as Q2 softly starts, Q3 must be turned on to provide the current path back to the mains.

A large negative current spike will also appear at the AC zero-crossing if the Q3 MOSFET is turned on too late after the soft start of Q2 is completed as detailed in [2].

EXPERIMENT RESULTS

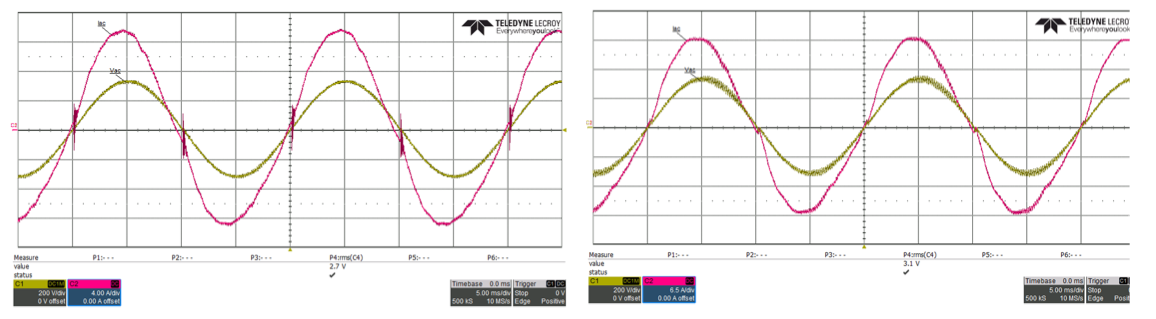

Figure 7 shows the input current waveform around the AC zero-crossing with and without the soft start.

Note that, since the ''1-D'' is very small when Q2 first turns on, it becomes even smaller and tends to zero when multiplied by the soft start factors. Depending on the used gate driver, Q2 may stay off for a couple of PWM cycles until the ''1-D'' term becomes larger than the gate driver’s minimum PWM on time. This results in a remaining, but very small, positive, and negative current spike at each AC zero crossing.

Figure 7: Input current spikes at AC zero crossing with and without soft start method (red: IAC, green: VAC). Left) Traditional control without soft start, right) With soft start method.

The MOSFETs’ control sequence explained in the previous section was implemented and tested in the 3.6 kW TP-PFC EVK. From the test results, without this control method, both negative and positive current spikes are present. The application of the soft start to both active and synchronous MOSFETs, as well as turning on the low frequency MOSFETs at the right moment, has shown better current waveforms and helped achieved much lower THD.

SUMMARY

The presented TP-PFC EVK shows a high performance in major design aspects, including control features and a high efficiency, reaching 98.5% while including all on-board power consumption of the auxiliary power supplies and the cooling fan. Both low on-state resistance and low switching loss of the 4th generation SiC MOSFETs helped in the achievement of such performance.

The results demonstrate how suitable these new products are for many power conversion applications such as for example server and data center power supplies, telecommunication, industrial power supplies (SMPS), energy storage systems as well as inside electric vehicles (e.g., OBC) where high power density, efficiency, simple gate circuit and short circuit robustness are required.

By Abdelmouneim Charkaoui, Christian Felgemacher & Jochen Hüskens, ROHM Semiconductor

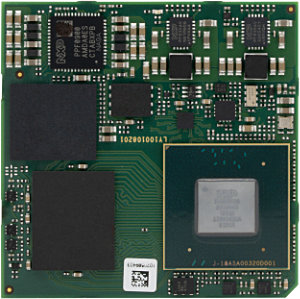

Tria Technologies on julkaissut uuden OSM-LF-IMX95-moduulin, joka tuo tekoälylaskennan suoraan piirilevylle juotettavaan muotoon. Moduuli perustuu NXP i.MX 95 -sovellusprosessoriin ja noudattaa Open Standard Module eli OSM 1.2 -määrittelyä.

Tria Technologies on julkaissut uuden OSM-LF-IMX95-moduulin, joka tuo tekoälylaskennan suoraan piirilevylle juotettavaan muotoon. Moduuli perustuu NXP i.MX 95 -sovellusprosessoriin ja noudattaa Open Standard Module eli OSM 1.2 -määrittelyä.

Virtaamamittaus on monissa laitteissa kriittinen mutta usein ongelmallinen toiminto. Perinteiset mekaaniset anturit kuluvat ja jäävät sokeiksi pienille virtausnopeuksille. Ultraäänitekniikkaan perustuvat valmiit moduulit tarjoavat nyt tarkan, huoltovapaan ja helposti integroitavan vaihtoehdon niin kuluttaja- kuin teollisuussovelluksiin.

Virtaamamittaus on monissa laitteissa kriittinen mutta usein ongelmallinen toiminto. Perinteiset mekaaniset anturit kuluvat ja jäävät sokeiksi pienille virtausnopeuksille. Ultraäänitekniikkaan perustuvat valmiit moduulit tarjoavat nyt tarkan, huoltovapaan ja helposti integroitavan vaihtoehdon niin kuluttaja- kuin teollisuussovelluksiin.